I spent last summer in Nopolo in Baja California Sur diving

the islotes and headlands that I could reach with my kayak. I dove early in the

morning, the coolest part of the day, and often saw the sunrise from the

Transpeninsular Highway on my way to places where I could launch a boat. The Sea of

Cortés was warm (low 80s°F) and gin-clear (visibilities greater than 40-50 ft).

By mid-afternoon the heat was oppressive, weighing on me like a thick blanket;

I spent them studying Spanish by the pool or visiting friends in homes where

air conditioners and fans ran all day.

|

| Santa Rosalía harbor with abandoned copper smelter (tall smokestacks) |

Several divers told me that the best visibility in the

Sea of Cortés occurred during the summer and I had to find out if that was true.

The heat of Mexico in the summer was too much for Rande; she spent it at 7,000

feet in northern New Mexico looking for a place for us to live. We’ve been on the

road since we sold our house in northern Colorado in 2013 and she was tired of

living out of a truck always on the go. Near the end of the summer, with her father seriously

ill, the plan was for me to return to New Mexico, meet Rande and drive us to Washington

to be with her family.

|

| Santa Rosalía harbor pangas at sunrise |

I’ve driven the 1,100-mile route from Baja California Sur to

New Mexico (and vice versa) several times: drive north on the Transpeninsular Highway (Federal Highway 1) to Santa Rosalía, take the ferry 100 miles across the Sea of Cortés

to Guaymas on the mainland, then drive north on Federal Highway 15 through Hermosillo

and cross into the U.S. at Nogales. In late August, I made reservations over

the phone for the Sunday ferry a week hence. It runs three times a week and carries about a dozen vehicles, so reservations are recommended (link).

|

| Santa Rosalía harbor pier with brown pelicans |

I arrived in Santa Rosalía mid-afternoon the following

Sunday and purchased a ticket for the truck and one for me for the 8 PM

departure. I passed the time in the parking lot at the ferry terminal chatting

with an older gringo who was returning to his home in Guaymas. At 8 PM, we were

still waiting to load. I went inside the terminal and asked the woman at the

ticket window when the ferry was leaving. She said there was bad weather (“mal

tiempo”) in the Sea of Cortés and that the ferry would leave at 7 AM the next

morning and to return to the terminal at 5 AM.

|

| Sailboats in Santa Rosalía harbor |

I found a room at Las Casitas, a nice hotel overlooking the Sea of Cortés south of Santa Rosalía, and was back at

the ferry dock at 5 AM. The

captain was walking across the parking lot and I asked him when we were leaving. He

recognized me from previous crossings – the gringo with a kayak on his truck. He

said that winds in the middle of the Sea of Cortés were gusting over 20 knots (23 mph) and

the seas were up to 2 m (6 ft), but the Mexican weather service expected the

winds to die and the seas to drop by noon, which was when we would depart. I

had time to kill, so I grabbed my camera and took a walk around the harbor as the

sun was rising.

|

| There are eight Sally Lightfoot crabs on the rock before the wave crashes... |

|

| ...and eight Sally Lightfoot crabs on the rock after the wave recedes |

|

| Abandoned copper smelter |

Santa Rosalía was founded in 1884 by Compagnie du Boleo, a

French mining company that operated the Boleo Mine (primarily copper, but also cobalt,

manganese and zinc) from 1885 to 1954 (link).

Copper was discovered near Santa Rosalía by a rancher in 1868, but mining activities were limited until

the arrival of the French. To encourage economic growth in Mexico, President

Porfirio Díaz implemented policies that favored mining, including granting a 50-year

tax waiver to Compagnie du Boleo. In return, the company was required to build

a town, which they named Santa Rosalía. The company installed an electrical

power plant in the mid-1890s and became the second city, after Mexico City, to

have electricity. By 1900, the company was producing 90% of the

copper in Mexico (link; link).

|

| Palo verde growing in abandoned smelter building |

Primarily underground mine, El Boleo operated continuously from 1886 to 1972 and an estimated 18 million tons of ore were smelted. Compañía Minera Santa Rosalía, a Mexican mining company, took over the mine after the French left to prevent the town’s economic collapse. They used “…the same (rather archaic) equipment and process used by the French” until the 1980s when the mine closed due to lower-grade ore and old technology. After 1972, underground and open-pit mining were conducted sporadically until the copper smelter closed in 1985 (link). El Boleo comes from boleite, a halide-containing mineral first collected as an ore of silver, copper and lead near Santa Rosalía (link; link).

|

| Boleite crystals from El Boleo (photo: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com - CC-BY-SA-3.0) (the sample is 2.5 in tall) |

Santa Rosalía, a town of about 12,000 people, is known for its French architecture and the

Iglesia de Santa Bárbara, a metal church designed by Gustave Eiffel for a country in Africa. The church was never shipped and one of the directors of Compagnie du Boleo purchased it in Brussels in 1897 and had it shipped to Mexico (link; link).

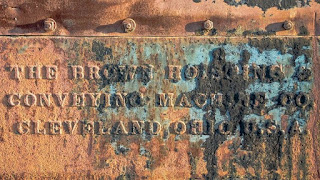

The smelting facilities were not torn down and are near the harbor in the center of town. Across the street from the smelter is an old, rusted crawler

crane with a shovel. The builder’s plate on the cab says: “The Brown Hoisting

& Conveying Machine Co. Cleveland Ohio U.S. A.” The company was founded in

Cleveland in 1885 and "...became the largest company in the world dealing exclusively in cranes and materials handling machinery, filling orders for all types of industry..." (link).

It was known as Brown Hoisting Machinery Company from 1900 to 1927 when it merged

with Industrial Works of Michigan to become Industrial Brownhoist Corporation. “Cie de

Boleo, Mexico” appears in a 1901 catalog of products (link),

so the crane in Santa Rosalía likely predates 1900. The earliest cranes were

powered by steam; this appears to be a

steam-powered crane.

|

| Builder's plate |

In the courtyard of the smelter, there’s a plaque commemorating

the “Rehabilitación del Edificio de la Luz” (Restoration of the Building of the

Light) dedicated by the governor of Baja California Sur and the president of the municipality

in 2008. There were two interpretive signs in a room inside the largest building proclaiming it the Plaza Museo “La Fundición” (Foundry Museum). The room had been cleared of debris and the signs outlined the smelting process. Unfortunately, the

machinery was not labeled, so I couldn’t determine which machine did what. Several

workers were clearing debris from a larger, adjoining room inside the old

smelting building; they ignored me as I walked around taking pictures.

In the

smelting process, copper-bearing ore is crushed and the waste rock (gangue) is

removed. What's left is roasted to convert sulfides to oxides, which are

smelted with heat and a chemical reducing agent, such as coke, to produce

copper matte (molten metal) (link). According

to the interpretive signs, the process to obtain copper blister (99% pure

copper) was fusion and conversion in a reverberatory furnace with the copper

ore (85% oxidized and 15% sulfides), gypsum, carbon and silica ore. The grade

of the copper matte (molten copper sulfide phase) was 50-55% and it came out of

the furnace at 1100-1150°C. Molten slag came out of the front of the furnace at

1250°C; it was cooled in a stream of seawater, stored in bins and loaded into

dump trucks for disposal. Slag blocks were used to build the breakwater around the harbor (link).

|

| Foundry museum |

Prior

to the disposal of waste gases from the furnace, waste heat from combustion was

recovered to power boilers that generated part of the energy for the smelting

operation, including the blowing machine that produced air for conversion of

the copper matte.

During

conversion of the copper matte to blister copper, air was blown through and

silica ore was added to the converter. The air oxidized iron sulfides and the

iron oxides bound to the silica to form the slag. The conversion products

included: blister copper (99.3-99.5% purity), slag (2-5% copper) and gases.

Temperatures in the converter were 1250-1300°C, which maintained copper as a

liquid. The liquid was poured into molds, cooled and stored. Roasting and

reverberatory furnace smelting dominated world copper production until the 1950s (link).

More recently, Baja Mining, a Canadian company (link),

began exploring El Boleo and estimated that it contained 534 million tons

of ore that was on average 0.59% copper, 0.051% cobalt and 0.63% zinc. El Boleo was reopened in 2014

by Minera y Metalúrgica del Boleo, a partnership between a consortium of Korean

companies, which own 90%, and Baja Mining, which owns 10%. The underground and

open pit mines have an estimated lifespan of 22 years (link).

Its first shipment was 1,919 metric tonnes (2,115 U.S. tons) of copper cathode (>99%

pure) in July 2015 and a further 2,750 tonnes (3,031 tons) in October (link).

As I

was leaving the smelter, a slim, unshaven man with well-worn clothes approached

me asking if I wanted a tour of the building. I thanked him, gave him some

pesos and said I had to catch the ferry to Guaymas.

We left Santa Rosalía mid-afternoon Monday, 18 hours

behind schedule, and arrived in Guaymas around midnight. It was the ferry

ride from hell. I had made five crossings on this ship in the past two years

and it was never full of cars or people. On this trip, the car deck was full

and there were upwards of 100 people on the boat (and only two gringos). They loaded the walk-on

passengers first, so by the time I got to the main salon, every seat was taken. It was the only publicly-available room on the boat that had air conditioning; even the deck crew came in there to cool off during the trip.

To make matters worse, the ferry company had removed about a third of the seats,

which were being replaced with new ones, but the new seats were stored

unwrapped in the smaller salon and hadn't been installed. People were sitting

on the floor when I got to the main salon. I couldn't imagine 11 hours across

the Sea of Cortés sitting on the bare floor!

Some people placed their bags, jackets and blankets on empty

seats to save them for friends and family, or so they said, but some wanted the extra seats for space to lie down. I tried to cajole an older couple with their

middle-aged son sitting on a bench at the back to make room for me. They told

me they were saving the seats for niños, who it turned out didn't exist. They

must have felt guilt for refusing to move their bags so a gringo viejo (old gringo) could sit down. Eventually they moved their bags, inched closer together

and I sat down.

The young woman on the other side of me had three kids, who

kept coming and going; they couldn't sit still until their sugar high had worn off and they crashed on the bench and on the floor. She fell asleep against

my shoulder. The crew showed bad U.S. movies dubbed in Spanish – Fast and Furious 7 (I didn't know that

those movies were so popular; this one stunk), the Tooth Fairy starring The Rock (a stupid movie, but surprisingly, he's not a bad slapstick comedian)

and several more whose names I don't remember, but they all involved violence

and mayhem. About an hour from Guaymas, I went down to the car deck and stood at

the rail on the stern (the only place with a breeze) until we arrived. I got a hotel room about 1 AM at the first hotel I passed.

I was up before sunrise Tuesday and on the road. The McDonald's where I hoped to get coffee didn't open until 8 AM, so I bought a large, weak

coffee at the first Oxxo (Mexico's 7-11) on my way out of town. The drive to Nogales was easy; Federal Highway 15 is

four lanes all the way to the border, except for Hermosillo, where road crews have

been widening the incredibly horrible, two-lane route that winds through barrios. The 18-wheel semis, long-haul buses, local

traffic and stoplights make it a driver’s nightmare.

The valleys in northern Mexico above 2,000 feet were green and lush from the summer monsoons. I crossed the border without being searched and drove to Truth or Consequences, NM, almost 700 mi from Guaymas, and found a motel; I arrived in Taos the next day.

Postscript: Information on the geology of El Boleo and current mining processes and operations can be found here, here, here and here. Mining in Baja California Sur is controversial. Landowners and ranchers that rent their land to the mining companies often favor mining. Local ranchers and farmers concerned about water contamination often oppose mining. There have been significant street protests in cities and towns in Baja and citizen petitions against mining submitted to the federal government (link; link; link; link).

|

| Desert near Tucson |

Postscript: Information on the geology of El Boleo and current mining processes and operations can be found here, here, here and here. Mining in Baja California Sur is controversial. Landowners and ranchers that rent their land to the mining companies often favor mining. Local ranchers and farmers concerned about water contamination often oppose mining. There have been significant street protests in cities and towns in Baja and citizen petitions against mining submitted to the federal government (link; link; link; link).

No comments:

Post a Comment